About Shorebirds

What is a Shorebird?

Shorebirds are a diverse group of birds in the order Charadriiformes, including sandpipers, plovers, avocets, oystercatchers, and phalaropes. There are approximately 235 recognized species of shorebirds worldwide, 87 of which regularly occur in the Americas for all or part of their lifecycle. 52 species have breeding populations in North America, and 38 species have breeding populations in Central America, the Caribbean, and South America.

Most shorebirds are found near water, but several species prefer habitats far from shore. Many species are long-distance migrants, traveling from breeding grounds in the Arctic tundra to non-breeding grounds in southernmost South America (and back!) each year.

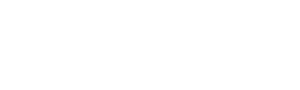

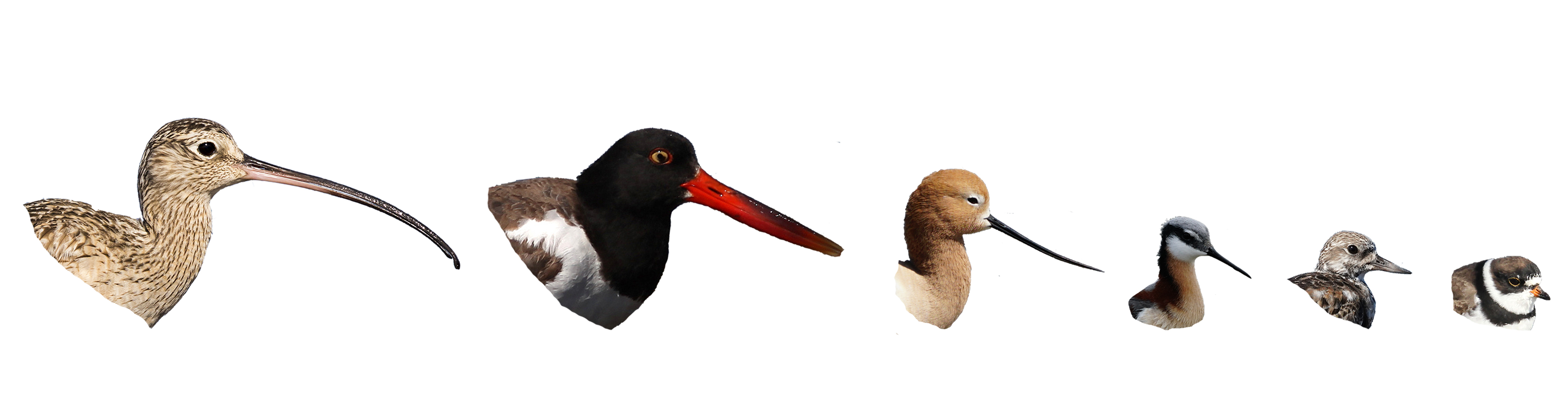

Shorebirds are found from intertidal mudflats, sandy beaches, and rocky coastlines to freshwater wetlands, grasslands, plowed fields and flooded agricultural lands. They feed mainly on mollusks, small crustaceans, marine worms, and insects. Shorebirds span a variety of sizes, bill shapes, and leg lengths, each species uniquely adapted to access their preferred foods in their specific habitats.

The Annual Journey

Marathon Migrants

Shorebird migrations are the endurance marathons of the natural world. For Red Knots, Buff-breasted Sandpipers, and Hudsonian Godwits — species which breed in the Arctic and winter at the southern tip of South America — migrations can span 20,000 miles a year.

Finding the Feast

Why risk a migration requiring such incredible endurance? The answer may be as simple as “dinner.” Shorebirds’ remarkable hemispheric travels coincide with the occurrence of a predictably abundant food supply at each stopover.

Consider the case of the rufa Red Knots: their nesting season syncs with the brief boom of insect life during the Arctic summer; as that food source diminishes, they head south to feast on the tidal flats of the Atlantic coast.

Their northbound journey is timed to coincide with the spawning of horseshoe crabs, particularly at the Delaware Bay. The horseshoe crab eggs are high in fat and protein to help the Red Knots double their weight, fuel for their last leg before returning to the Arctic.

Chasing Daylight

Traveling thousands of miles, shorebirds move as their current climate becomes harsh and challenging. They move on to places where the climate is more benign and less stressful for them. For example, in June, Arctic breeding grounds offer 24 hours of sunlight. Having double the daylight hours gives shorebirds that much more time to feed and store energy. Food is the constant driving motivation, and for these hemispheric migrants, departure time for the next journey is never far off.

Protecting the Rest Stops

In their global pursuit of food and breeding grounds, home is nowhere, yet everywhere. As a result, shorebirds are difficult to track, monitor, and protect. The stopover sites, where shorebirds are congregating in large numbers to rest and recover, are essential to protect and understand for successful conservation.

Departing Patagonia

Like Nearctic shorebirds fleeing the cold winters of the northern hemisphere, several Austral shorebirds flee the cold winters of the southern hemisphere. Characteristic austral species like the Rufous-chested Dotterel and Least Seedsnipe are just two of these Patagonian breeders that move north after breeding. The enigmatic Magellanic Plover is more of an altitudinal migrant, leaving lagoons on Andean plateaus to winter along estuaries of the southern Atlantic coast. Many of these birds depend on the same stopover sites as their Nearctic relatives.

Page photos top to bottom: Brad Winn, Laura Chamberlin, Shiloh Schulte, Brad Winn, Arne Lesterhuis.