Laguna Madre is the only WHSRN site that spans two countries. From southern Texas to the state of Tamaulipas, Mexico, it is one of only six hypersaline lagoons in the world – a vast expanse of shallow, wind-driven wetlands separated from the Gulf of Mexico by a long strand of skinny barrier beaches. David Newstead has been studying the seasonal movements of Red Knots (Calidris canutus) on the Texas side of the Laguna since the early 2000s. Flocks of knots were mostly seen on the Gulf beaches in fall and spring, but they seemed to disappear every winter. Where did they go? Did they belong to the rufa subspecies that breeds in the eastern Canadian Arctic? Or the roselaari population that breeds in northwest Alaska and Wrangel Island, Russia?

Newstead, who directs the Coastal Bird Program for the Coastal Bend Bays & Estuaries Program, began closely monitoring Red Knot movements in Texas during the winter of 2009, working on a project led by Larry Niles and colleagues that studied knots on Delaware Bay. That year, their team found close to 2000 individuals. “This was the impetus to investigate further,” Newstead said. It was time to figure out whether these birds were just passing through, or whether they spent the whole winter in Texas.

David Newstead with Red Knot 198, a Louisiana-tagged bird whose geolocator data indicated it was a rufa Red Knot that wintered in Ecuador. Photo: Barbara Keeler.

The common hypothesis at the time was that the wintering population of roselaari Red Knots was mostly in northwest Mexico. “This left a lot of questions,” Newstead explains, “because there were records of knots further south on the Pacific coast, but no resights were being reported of marked roselaari, and in Texas we weren’t seeing any rufa marked at the major Atlantic flyway sites.” Newstead collaborated with Larry Niles and his team tagging Texas Red Knots with geolocators in the fall of 2009, and by 2011, they were sure that some individuals were staying put on the Gulf Coast all winter. From 2012-2014, Newstead used aerial radiotelemetry to find out that some of the knots that flocked to the Gulf beaches every spring and fall were only moving as far as the saline lagoons on the other side of the barrier islands. Seasonally high water levels push knots to the coastal beaches during fall and spring, but when water recedes in winter, they can forage in the wetlands of Laguna Madre – a landscape so vast and hard to survey that it’s no wonder scientists thought the birds had flown much further away.

Left: A flock of Red Knots on the Gulf Coast. Photo: Eric Hernández Molina. Right: Red Knot 2K8. Photo: Liz Smith.

In the years since finding this winter hotspot, Newstead and colleagues have continued to make new discoveries about Gulf Coast Red Knots through tagging efforts in Texas, and thanks to partnerships with the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries and the Barataria-Terrebonne National Estuary Program, the work has also expanded into Louisiana. Since 2009, Newstead and this team of collaborators has deployed and retrieved over 150 geolocators, tracked over 75 birds through the winter using radiotransmitters, put out 50 Motus nanotags, and tagged nearly 1000 individuals with unique colored leg flags, revealing the migratory paths and breeding territories of several Red Knots – as well as discovering connections with many other WHSRN sites. Geolocator data has shown that the wintering population in Texas seems to be mostly rufa Red Knots, while both rufa and roselaari subspecies stop at Laguna Madre in spring. Tracked knots that spent the winter on the Gulf are primarily mid-continent migrants, sometimes stopping at Chaplin and Reed Lakes, part of a WHSRN complex in Saskatchewan. Several knots that spent the winter in Texas headed to Nelson River in the spring, a subarctic stopover before reaching breeding grounds further north on Hudson Bay. Curiously, Red Knots tagged on the Delaware Bay have also been tracked to Nelson River, highlighting that different wintering populations are using the same staging area.

For Red Knots that were passage migrants through Texas, Newstead’s geolocator and flag resight data have unveiled new links between the Gulf Coast and other WHSRN sites in the Pacific Flyway. Knots that Newstead tagged in Texas and Louisiana have stopped at the WHSRN Site Ojo de Liebre-Guerrero Negro in northwestern Mexico and on the coast of Peru at the Reserva Nacional de Paracas. They’ve also wintered on Panama Bay, and all the way on Chiloé Island in southern Chile.

The geolocator tracks for the roselaari Red Knot 6J3 (tagged in 2012), that bred in Alaska, migrated south down the Pacific Coast of the United States and Mexico, paused in Peru, and then flew to Chiloé Island for the duration of the boreal winter. In spring, 6J3 flew directly (over six days!) from Chiloé all the way to the Gulf Coast of Texas. Map courtesy of David Newstead.

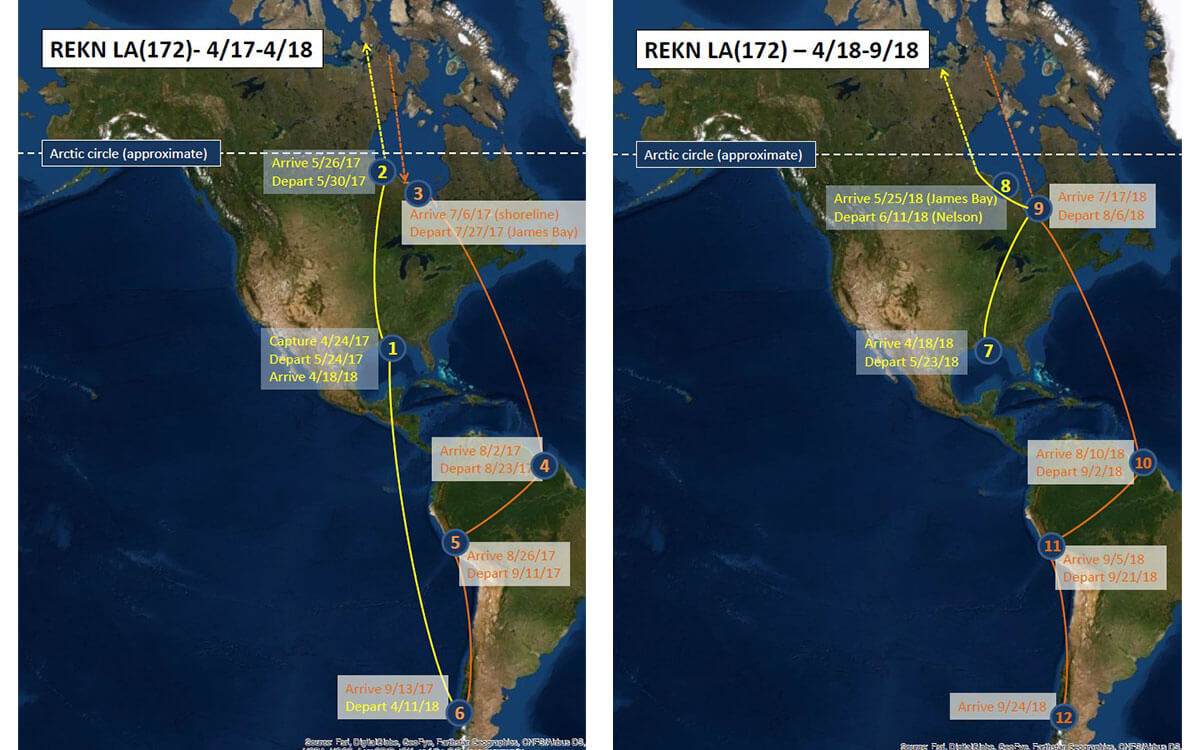

Some birds, like the two individuals with geolocators that wintered on Chiloé, raised more questions than answers. When Newstead recovered each of these devices, the tracks revealed that one of these birds was rufa and the other roselaari. The roselaari (REKN 6J3, tagged in 2012) bred in Alaska, migrated south down the Pacific Coast of the United States and Mexico, paused in Peru, and then flew to Chiloé Island. The rufa individual (REKN 172, tagged in 2017) bred around Hudson Bay, flew directly from there to the northeastern coast of South America, crossed over to also stop in Peru, and continued from there to Chiloé. Both of these birds flew direct (over six days!) from Chiloé all the way to the Gulf Coast in spring – the rufa to Louisiana and the roselaari to Texas. These two knots may be anomalies in Newstead’s data set, but they highlight the need for further research to better understand the migration patterns of rufa and roselaari birds that converge on the Gulf Coast.

The geolocator tracks for the rufa Red Knot (tagged in 2017) that bred around Hudson Bay, flew directly from there to the northeastern coast of South America, crossed over to stop in Peru, and continued from there to Chiloé. In spring, 172 flew directly (over six days!) from Chiloé all the way to the Gulf Coast of Louisiana. Map courtesy of David Newstead.

How can these discoveries inform more effective conservation action for Red Knots? Not only is the Gulf Coast of Texas and Louisiana a migratory stopover for many more Red Knots than previously known, but some are combining their fall, winter and spring into one stop, depending on one area for more than 75% of the year. In addition to Laguna Madre, four other WHSRN sites in Texas help conserve a large stretch of this coastline for shorebirds, and continued research could provide enough data to nominate the first WHSRN site in coastal Louisiana. With new understanding that this area is shared by both rufa and roselaari Red Knots, continued research is crucial to discern the conservation status of each of these subspecies.

Red Knot 107 in hand. Photo: Barbara Keeler.

“This spring we’ll be deploying GPS Argos tags on Red Knots in both Texas and Louisiana,” said Newstead, describing plans for 2020. “This will reveal higher accuracy location data at a much finer scale than previous geolocator studies. We’ll use the GPS data, as well as genetic samples, to determine breeding locations and help sort out subspecific relationships.” Even as Newstead’s Red Knot research reaches for new technology, the simple act of reporting resight data is as important as ever. “Honestly, with so little historical information from Central and Pacific South America, I have learned a lot more about the species ecology and local conditions from getting in touch with people who reported birds in these locations than I could have otherwise. It has been invaluable.”

Does your WHSRN site already conduct regular shorebird monitoring? Increasing survey efforts for flagged birds and submitting resight data could help reveal new stories about migratory connectivity, and highlight new connections between WHSRN sites that share the same shorebirds. “This has been a team effort from the beginning,” Newstead says. “Together we will continue to pursue further knowledge that can help the conservation of Red Knots.”

Cover Photo: Red Knot 198. Photo: Eric Hernández Molina.