This article was first published on the Shorebird Science blog

In 2019, the Neotropical Migratory Shorebird Conservation Act (NMBCA) of the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service financed a comprehensive survey of shorebirds in Altiplano Wetlands of Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, and Peru. The project was implemented in February 2020 by the WHSRN Executive Office in collaboration with the High Andean Flamingo Conservation Group (GCFA). One WHSRN staff member, Arne Lesterhuis, went on a road trip from his residency in Asuncion (Paraguay) to join the surveys of project partner BIOTA in the Altiplano of Bolivia. He was accompanied by Garry Donaldson of Environment and Climate Change Canada. Here is a brief report of their eight-day adventure. Enjoy!

Although I have lived next to Bolivia for over 15 years, I’ve actually never had a chance to visit. For many years, I have been conducting fieldwork in the Paraguayan Chaco, west of the large Paraguay River, and got close to the Bolivian border a couple of times, but never further. So a road trip to Bolivia to implement shorebird surveys was a perfect opportunity to get to know the country, its nature, and its birds.

Bolivia, being a landlocked country like Paraguay, might not sound like a place where you would go for shorebirds; but you might be surprised that no less than 38 species have been documented there (nearly 40% of all regularly-occurring shorebirds in the Americas!), including 21 Nearctic migrants and 17 resident species.

Foraging Wilson’s Phalaropes at Lago Poopó. Photo: Garry Donaldson

The saline lakes in the Altiplano of Bolivia (and also Argentina, Chile, and Peru) are known to hold high importance for significant numbers of migrating and wintering Nearctic shorebirds. These High Andean wetlands encompass the core wintering range of Wilson’s Phalarope (Phalaropus tricolor), with numerous wetlands representing flocks of 100,000 individuals or more! For that reason, Wilson’s Phalarope was one of the focal species of our project. We implemented surveys simultaneously during the first days of February 2020 throughout its winter range (in all four countries) to be able to set an updated estimate of the species’ population. Currently, this is set at 1,500,000 individuals but has not been revised for over four decades. Numbers of several other Nearctic shorebirds also occur in high numbers in the Altiplano, including the Baird’s Sandpiper (Calidris bairdii), and both Greater and Lesser Yellowlegs (Tringa melanoleuca and T. flavipes). Apart from increasing our knowledge regarding shorebird abundance and distribution in the High Andes, we also hope to trigger increased interest in monitoring these interior wetlands more regularly and recruit new volunteers for the International Shorebird Survey (ISS).

But, I’m already pretty familiar with most of these Nearctic species…and, to be honest, I was much more interested in finding some of the Altiplano specialties like the Puna Plover (Charadrius alticola), Andean Avocet (Recurvirostra andina) and Andean Lapwing (Vanellus resplendens). I was also excited to find the more cryptic species like snipes (Gallinago sp.), seedsnipes (Thinocorus sp.), and the curious Diademed Sandpiper-Plover (Phegornis mitchellii). Information on these species is scarce; some are quite common, whereas others are much harder to find.

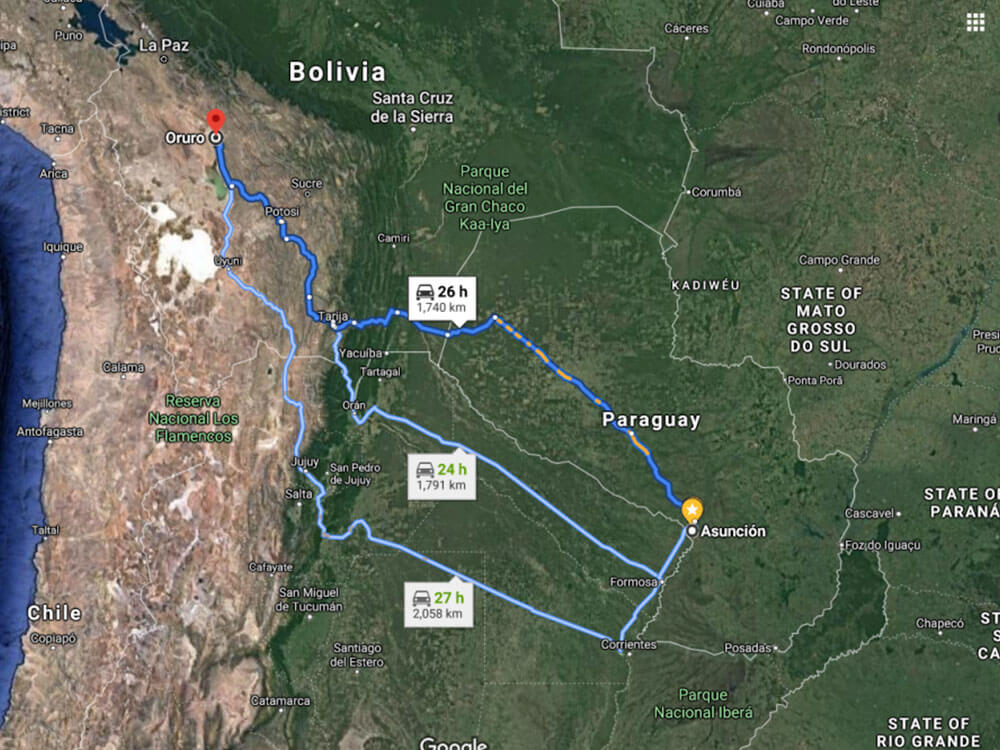

It would take us about two days and just over 1,700 km (1,050 mi) to get to our destination: Oruro, Bolivia

My travel companion, Garry Donaldson, who had enthusiastically signed up for this adventure, arrived in Asuncion on January 28, 2020. We would travel in my 2011 Nissan Frontier, which had endured many field trips already, so I trusted we would be fine. Our travel destination was Oruro, where we would meet up with Sol Aguilera and Magali López of partner organization BIOTA. Oruro lies approximately 1,700 km from Asuncion and we calculated that, in theory, it would take us about two days if all went smoothly and without much stopping.

We set out on the morning of the 29th and headed directly towards the Private Reserve Cañada el Carmén of Guyra Paraguay, the national BirdLife Partner in Paraguay. This reserve is 700 km (430 mi) from Asuncion near the Bolivian border. We arrived without problems; unfortunately, though, due to heavy rains the night before, the remote Paraguay-Bolivia border control had a blackout and we were stuck for approximately five hours. We took this time to enjoy the local fauna (stray dogs and House Sparrows). When we finally were able to cross and continue our adventure, it was already noon on our second day…so it would be hard to get to Oruro that same day with over 1000 km (620 mi) to go.

The first mountain range we saw shortly after crossing the Paraguay-Bolivia border. Photo: Arne Lesterhuis

To my surprise, it was only after just a couple of kilometers over the border that the terrain already started to elevate; we could even see the first mountain range! But then, when we were close to the first town, Villamontes, where we could get gas, we stumbled upon a roadblock made of a pile of rocks. Right in the middle of the road. We learned that it was set up by locals unhappy with the government. Fortunately, the locals were kind enough (after being paid) to show us an alternative road next to the main road. When we finally arrived at Villamontes, we learned that it would not be easy to get diesel for a foreign truck, as there was a limit on liters per gas station and even a higher price for foreign vehicles. This meant we needed to remain vigilant and think creatively to keep the tank full; and, thankfully, we didn’t run into any gas-related problems the entire trip.

After Villamontes, the landscape changed completely. Still a ways away, and only at 388 m a.s.l. (~1,300 ft), the climb towards Oruro (3,700 m/12,700 ft a.s.l.) had started. We drove on all types of roads (tarmac, pebble, dust) and each turn had an even more spectacular view than the last. The photos speak for themselves but know that these are just a few of all the photo-worthy views out there. It’s a pretty amazing world.

Due to the blackout at border control, the roadblock, and the fact that the truck was not used to steep climbs (forcing us to make occasional stops to cool off the engine, but who cares if you are being kept entertained with impressive landscapes?), we weren’t making much progress so we had to stay in a town called Tarija (1,866 m/6,100 ft a.s.l.). On the third day, we had to make the biggest climb all the way up to Potosi at 4,067 m a.s.l. (13,300 ft). You can imagine that did not go very fast either, so when we arrived at Potosi, we called it quits and would continue the next day. It was on this day when I started feeling the elevation; just climbing the stairs in the hotel was like running a marathon!

The changing landscape: impressive views on our way to Oruro.

Although we had seen great birds along the road—Mitred Parakeets (Psittacara mitratus), Yellow-collared Macaws (Primolius auricollis), Bare-faced Ground Doves (Metriopelia ceciliae), and Mountain Caracaras (Phalcoboenus megalopterus)—the fourth day finally brought us the first Andean shorebird; a pair of Andean Lapwings sitting near the road. Although they look and sound quite similar to the widespread Southern Lapwing (Vanellus chilensis), they are a completely different species (and a lifer for me)!

At Potosi, we had more or less reached the elevation of Altiplano, so we were pretty much done with climbing and finally reached Oruro early in the afternoon on February 1. It was still early, so we picked up Sol and Magali and went to our first lagoon next to Oruro, Lago Uru Uru, to start counting shorebirds. It was a great spot and we immediately started surveying. It was quite a busy start; over 2,000 Wilson’s Phalaropes feeding and flying among thousands of Chilean and Andean Flamingos (Phoenicopterus chilensis and Phoenicoparrus andinus). It was tough counting and we probably missed a number of individuals but, overall, we identified a total of 12 shorebird species, including Lesser Yellowlegs, Stilt Sandpipers (Calidris himantopus), Pectoral Sandpipers (C. melanotos), and Baird’s Sandpipers.

Although the highlight probably should have been the four Least Sandpipers (C. minutilla) and two Semipalmated Plovers (Charadrius semipalmatus) we saw, both being rare species in Bolivia, it was really the two Andean Avocets that I liked the most. These large, mostly white shorebirds with black wings and their characteristic black upturned bill are just stunning.

The stunning Andean Avocets. Photo: Garry Donaldson

Over the next couple of days, we drove around the large Lago Poopó, a huge lagoon south of Oruro which, together with Lago Uru Uru, is one of Bolivia’s eight Ramsar sites. The lagoon was quite dry so there were not a lot of shorebirds, nor flamingos, but the vast, short-vegetated plains surrounding Lago Poopó do attract many Baird’s Sandpipers and we counted a total of about 400 individuals—the most I have ever seen at one site.

Again I must confess that it was not the Baird’s Sandpipers that got most of my attention at Lago Poopó, but my very first Puna Plovers! A total of nine of these relatively large Charadrid plovers were scattered around in the area, easily overlooked as they blend in very well in their habitat. While driving on a dirt road to the next lagoon to count, we also saw some other resident species, including a Tawny-throated Dotterel (Oreopholus ruficollis) and the Grey-breasted Seedsnipe (Thinocorus orbignyianus). The seedsnipe was an especially great find; I had seen the similar but smaller Least Seedsnipe (T. rumicivorus) before in Patagonia, but never the Grey-breasted, which is much larger. Almost like a cross between a quail and a dove, seedsnipes truly are shorebirds as strange as they appear—and stunning ones, at that!

The Puna Plover. Photo: Garry Donaldson

The highest altitude at the lagoon was Laguna Huayñakhota situated in the Sajama National Park at over 4200 m a.s.l. (13,700 ft) (see header photo). Upon arrival, the elevation got to me and made me feel pretty bad for a while. Luckily, I acclimatized by the following morning and was ready to get back at it. It turned out that the night before had been very cold, so we needed to scrape ice off my truck’s windshield—a new experience for the Nissan—and I’m glad I had Garry as my companion as he seemed to be a seasoned windshield scraper. Laguna Huayñakhota did not have a lot of shorebirds but it did have a nice collection of High Andean waterbirds like the Giant and Andean Coot (Fulica gigantea and F. ardesiaca), Chilean, Andean, and James Flamingo (P. jamesi), and Andean Goose (Oressochen melanopterus), as well as some other great landbirds like the Lesser Rhea (Rhea pennata).

One of the final lagoons we visited was the remote Laguna Saquewa, situated relatively close to the Chilean border. We were surprised by the large number of flamingos and Wilson’s Phalaropes at this site. Surrounded by heavy clouds, we counted all the birds hoping we would stay dry; fortunately, it rained all around us, but not at the lagoon where we counting. A total of 15,216 Wilson’s Phalaropes was the final count, enough for the site to be declared a WHSRN Site of Regional Importance. A great count before starting to head back towards Oruro and then home to Paraguay.

Wilson’s Phalaropes with Lesser Yellowlegs and White-backed Stilts. Photo: Arne Lesterhuis

The trip was epic, better than I could have imagined; having Garry, Sol, and Magali with me was a great pleasure, and we had a lot of fun. The views were impressive, the wildlife was astonishing, and the shorebirds were numerous, all reasons to go back and do it all over again at some point in the future. Perhaps I’ll visit some lagoons that are even higher, like Lago Titicaca. And, for a birder, there is always a species that gets away, a species that will make sure you come back. In my case it was the Diademed Sandpiper-Plover—we did not find it on this trip but I trust I will get it on the next one.

After eight days of driving, we were back in Paraguay (less than 100 m/328 ft a.sl.) and Garry and I visited some saline lagoons in the Central Chaco where came across a few more Wilson’s Phalaropes. A nice way to end this great adventure.

Currently, all data gathered in the four countries we visited is being analyzed. This includes additional data from a large region covering the lowlands of Argentina where many Wilson’s Phalaropes winter. With all the data combined, we will have a better idea of the abundance and distribution of this and other Nearctic migrants that use the interior lands during the non-breeding season.

The survey team at one of the lagoons. From left to right: Garry Donaldson, Magali López, Sol Aguilar, and Arne Lesterhuis.

Cover Photo: An Altiplano lagoon at over 4200 m a.s.l. (13,700 ft), Sajama National Park. Photo: Arne Lesterhuis.