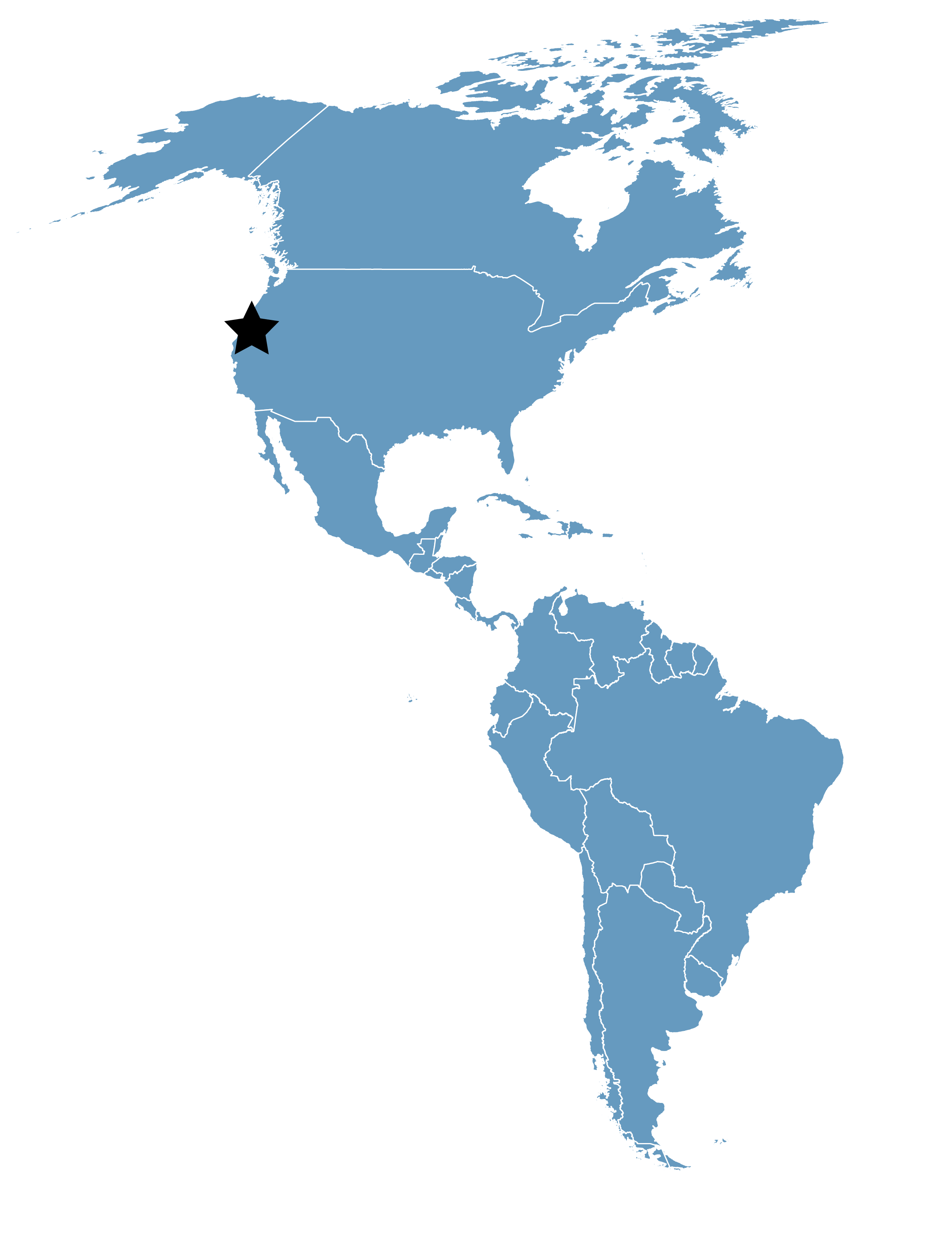

San Francisco Bay

Location

California, United States

Category

Hemispheric

Basis for Designation

Usage by more than 900,000 shorebirds annually.

Size

22,489 hectares (55,571 acres)

Date Designated

June 1989

Site Owner

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service

California Department of Parks and Recreation

California Department of Fish and Game Lands

East Bay Regional District

Midpeninsula Regional Open Space District

City of Mountain View

National Audubon Society

Site Partners

Point Reyes Bird Observatory

San Francisco Bay Joint Venture

Overview

San Francisco Bay holds higher proportions of the total wintering and migrating shorebirds on the U.S. Pacific coast than any other wetland. This estuary is an important wintering area for shorebirds that breed in a variety of arctic and temperate habitats. For example, three of the most common winter species, Dunlin, Willet, and Marbled Godwit, nest respectively in northern Alaska, the Intermountain Great Basin, and in Prairie Grasslands. The region also is important during migration, particularly for arctic-breeding species such as the Whimbrel, Western Sandpiper, and Short-billed Dowitcher. Numbers of these shorebirds in the region swell during migration periods, which extend primarily from mid-March to mid-May in spring and from mid-June until November in autumn. San Francisco Bay is the northernmost regular breeding area of the American Avocet and Black-necked Stilt on the Pacific coast of North America. About 10% of the U.S. Pacific coast population of the Western Snowy Plover breeds in the salt ponds of the South Bay.

Nearly half of California’s fresh water runoff finds its way to the San Francisco Bay Estuary.

Nearly half of California’s fresh water runoff finds its way to the San Francisco Bay Estuary. Sierra snowmelt and foothills Range rainfall are captured by the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers which meet with ocean tides entering through the Golden Gate. Once, the estuary sprawled over more than half-a-million acres of mudflats and salt marsh: the largest contiguous tidal marsh system on the Pacific Coast. San Francisco Bay wetlands have a long history of human alteration, including development of adjacent uplands and seasonal wetlands, dredging of tidal mudflats, and changes in salinity and tidal regime. Today more than 90% of the original wetlands have been lost to urban development; converted to agricultural fields or salt ponds; or degraded by pollution, exotic species introductions, and habitat destruction.

Despite the huge loss of natural habitat, the estuary’s remaining wetlands provide habitat for hundreds of thousands of shorebirds, waterfowl, and other water birds throughout the year.

Habitats in San Francisco Bay

Tidal flat is the primary foraging habitat of many of the region’s most abundant shorebirds, including the Black-bellied Plover, Semipalmated Plover, Willet, Long-billed Curlew, Marbled Godwit, Western Sandpiper, Least Sandpiper, Dunlin, and Short-billed Dowitcher. The main shorebird prey in the tidal flats are invertebrates, but many of these are introduced species that arrived through the release of ship ballast and other human actions.

Salt Pannes and Salt Ponds

Historically, about 645 ha of natural salt pannes, large open areas within the salt marsh vegetation, served as supra-tidal foraging and roosting sites for many shorebird species, and as nesting areas for plovers, stilts, and avocets. As the demand for salt rose in the mid-1800s, artificial salt ponds replaced the pannes.

Currently there are 13,943 ha of salt ponds in the estuary. The ponds vary in size, depth, salinity, and most importantly, invertebrate characteristics. Thus each type of pond varies in the vertebrate populations that are supported by the particular invertebrate assemblage found in that pond, resulting in the highest diversity of shorebird species of any other habitat in the Bay.

Though the habitat value of the once extensive vegetated marsh was lost when the ponds were formed, the ponds and levees within the salt complex became significant roosting and nesting sites for a wide variety of non marsh-dependent species, and the ponds themselves became important foraging areas for millions of shorebirds and other species of waterfowl, sea birds and other waterbirds.

LaRiviere Marsh.

Salt Marsh

Shorebirds use salt marsh to a lesser degree than tidal flats, but under some tidal conditions, roosting birds do use this habitat. The larger non-vegetated channels in salt marsh are used as foraging habitat by the same species that feed on tidal flats. Some species, such as the Willet, Whimbrel, Long-billed Curlew, and Least Sandpiper, also forage on marsh plains with sparse or low vegetation. Species such as the Willet, Least Sandpiper, Dunlin, and Long-billed Dowitcher use salt marsh as diurnal and nocturnal roost sites, possibly to provide some protection from predators such as owls.

There currently are about 16,265 ha of tidal marsh in the San Francisco Bay, a 79% decline from historic levels. Tidal marsh has been lost primarily to the development of salt ponds, agriculture land, and urban areas.

Snowy Plover. Photo: Stuart MacKay.

Threats

Shorebirds in the San Francisco Bay Estuary have experienced high levels of habitat loss, alteration, and degradation from agricultural and urban development over the past two centuries. Watershed run-off or point discharges have contaminated sediments or water at some inland and coastal locations. Mosquito abatement programs limit options for habitat management, especially the flooding of inland wetlands during summer.

The spread of exotic plants has reduced or threatens to reduce the extent of shorebird habitat. Spartina alterniflora has been introduced into San Francisco Bay from stock originating on the Atlantic coast of the US. This species grows at both lower and higher elevations in the intertidal zone than the native California cord grass (Spartina foliosa).

The ongoing introduction of many non-native invertebrates into the benthos of the Bay through ship ballast discharges and other human activities is regularly altering the composition of potential shorebird prey in an unpredictable manner. Other factors impacting, or potentially impacting, tidal flats and the invertebrates living in them include sea level rise, contaminants, oil spills, and proposed new ferry systems.

Nesting shorebirds in the region have experienced high rates of nest loss to introduced mammalian predators, especially the Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes), and to expanding populations of native predators, especially the Common Raven (Corvus corax).

Growing recreational use of beaches and wetlands appears to be causing increased disturbance of roosting and foraging shorebirds. The potential effects of climate change on shorebird populations, including changes in prey populations, and impacts to habitat quality, availability and extent, may be profound.

Marbled Godwit. Photo: Stuart MacKay.

Management Priorities

The recent acquisition of more than 16,000 hectares of salt ponds by state and federal wildlife agencies provides an unprecedented opportunity to restore large areas of contiguous tidal wetlands in South San Francisco Bay. Restoration of these complexes is now either underway (North Bay) or being planned (South Bay). Over 70 wetland protection, restoration, and enhancement projects have been completed, totaling more than 70,000 acres with another 60 projects currently under development or in process.