An Interview with Audrey DeLella Benedict, author of Pacific Flyway

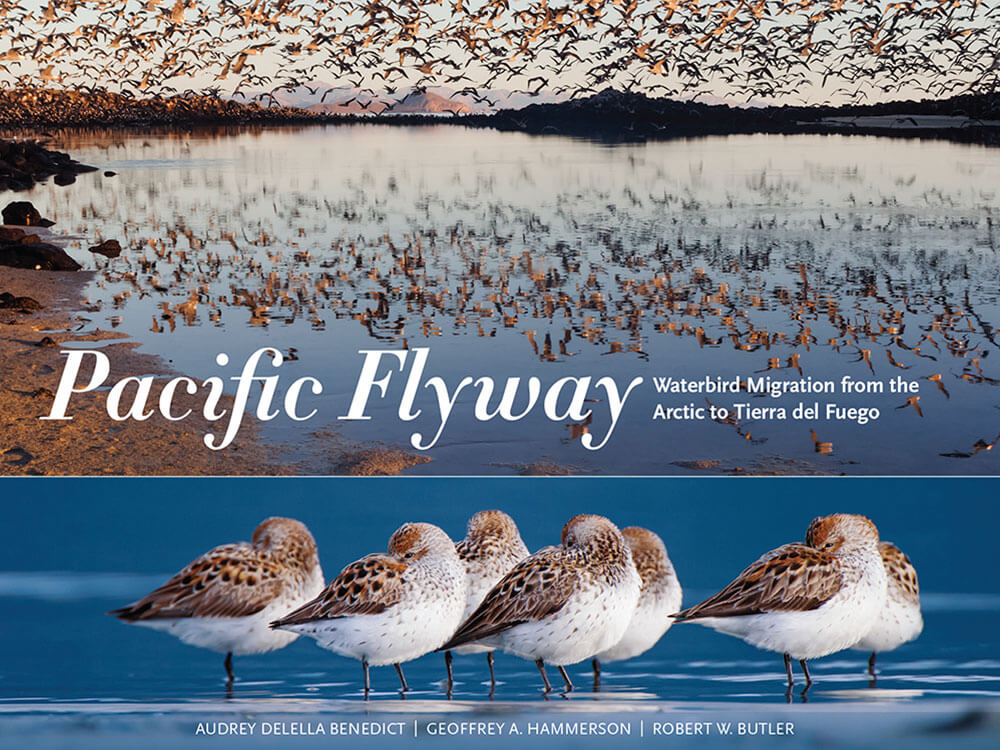

WHSRN’s Maina Handmaker had the opportunity to speak with Audrey DeLella Benedict, about her latest book, Pacific Flyway: Waterbird Migration from the Arctic to Tierra del Fuego, which she coauthored with Geoff Hammerson and Rob Butler. Pacific Flyway is at once a stunning photography book, a story of conservation and connections across a hemisphere, and a scientific account of migratory birds and their fascinating natural histories. Migratory shorebirds, of course, feature frequently in the book’s breathtaking images and compelling storytelling – and almost all of the sites mentioned in the book are WHSRN sites.

Audrey is the founder and director of Cloud Ridge Naturalists, a nonprofit natural history organization founded in 1979 with the mission to connect people to the natural world through education. In 2009, a nonprofit publishing arm, Cloud Ridge Publishing, was created. Published works, like Pacific Flyway are image-driven and incorporate power images with a compelling natural science narrative which aim to inspire stewardship and conservation activism.

Book cover “Pacific Flyway: Waterbird Migration from the Arctic to Tierra del Fuego” © Cloud Ridge Publishing

Maina Handmaker: What first sparked the idea for this project, and inspired you to bring this book to life?

Audrey DeLella Benedict: The idea, initially, was presented to me about three years ago by Gary Luke, who was then the Publisher and Managing Editor of Seattle-based Sasquatch Books (a Registered Trademark of Penguin Random House International). I had already done two books for them – the first was The Salish Sea: Jewel of the Pacific Northwest, which is also an image-driven book, and the second was a children’s version of the same. When Gary asked me to write an image-driven book about waterbird migration along the Pacific Americas Flyway, the unspoken challenge was to portray this spectacular biological phenomenon in a new and different way.

Given the vast scope of the flyway, and the task of doing justice to the stories of such a diverse array of waterbird species, I knew it would be a daunting but exciting assignment that I couldn’t do alone. So, joined by my research biologist coauthors, my approach was to interweave powerful images with a science-based narrative that highlights the myriad adaptations that enable these legendary travelers to crisscross continents and oceans — risking all in their unwavering quest to survive and reproduce. At its heart, Pacific Flyway is really a celebration of the magnificence, complexity, and mystery of waterbird migration, but every bit as important, it is also an urgent call for conservation action and stewardship.

MH: With education being such a core part of Cloud Ridge Publishing’s mission and your goals with Pacific Flyway, who are you most hoping this book will reach?

ADB: Our audience is really the interested general public. That can include people that are already birders, for example, in the case of Pacific Flyway, or people who are simply interested in natural history. It also includes young adults, as teenage years are such a formative time, as well as dedicated policy people in the conservation arena. Our books are very much admired by the scientific community as well, as I do not soft-pedal the science. I am in opposition to anything that remotely seems like a sound bite. I like to tell stories. That’s how I feel we get the message across most strongly. To me, linking good narrative descriptions, plus good science, with these powerful images is a magical combination.

Left: Western Sanpipers roost on beach. Photo: Florian Schultz. Right: Red Knot and chick on nest. Photo: Gerrit Vyn

MH: I agree that making science accessible is one of the most important things we can do to build a diverse and strong coalition for conservation. You don’t have to be a professional biologist to be aware, to care, and to learn how you can make a difference for conservation in your own place.

ADB: I really think too, as one reads through the book, they’ll see that a dominant theme in Pacific Flyway is global ocean health. I see migratory waterbirds as winged messengers. They’re giving us a checkup on the health of our ocean systems. A great number of people in the general population have absolutely no idea that their own lives, as well as every other animal on the face of this earth, is tied to the marine food web. It also drives climatic processes, and everything else. So, with ocean health declining in response to climate change, pollution of all sorts, and many other factors, people need to understand that not only are migratory birds at risk, their lives are at risk in all of this. We are connected. Ultimately, these little bits of what I think of as “jewels of information,” little intriguing bits of information like the stories in the book, help to bring these creatures to life in a way that you don’t do if you simply connect the dots on a migratory map. People have to be inspired by the extraordinary things these birds do – without any technology except what is in their brains. That’s the joy of it to me. And if I can relay that, then I think we’re creating stepping-stones to a well of information.

MH: We’ve talked about connection to these audiences, the need to connect to each other, and the way that these birds connect us all. So through the process of working on this book, are there specific examples of connections you made to people and places that were most inspiring to you?

ADB: Yes, absolutely. I’d like to thank Jim Chu, the Migratory Bird Program Specialist for the US Forest Service, International Programs. Jim was the first one to encourage me to attend the Western Hemisphere Shorebird Group meeting in Paracas, Peru, and he gave me an extraordinary introduction to a wonderful group of shorebird researchers. That opened up this incredible window to allow me to discover the scope and the diversity of research efforts going on throughout the Americas. That’s what inspired me to do some book research trips to important sites like Chiloé, for example, and the Copper River Delta. As well as a critical field trip to the Fraser River Estuary with my coauthor Rob Butler. My photography gives me, then, a base to really describe places that many people will never see. But I want to take them there through my words. I want to transport them. If I could have a little scratch and sniff section on a page, or a recording they could listen to, I would do that. Because to me it’s the whole sensual essence of place.

Chiloe Shorebird Mural. Photo: Audrey Benedict

MH: Maybe the kid’s version of this book can be the scratch and sniff edition!

ADB: [Laughs.] Yes! I’d like to see a junior version of Pacific Flyway. It’s just so powerful to see kids respond to these types of things. I’m on the board of the SeaDoc Society, which is the research and outreach arm of the University of California at Davis’ Wildlife and Veterinary Medicine Program. Dr. Joe Gaydos, SeaDoc’s Chief Scientist, and I co-authored The Salish Sea: Jewel of the Pacific Northwest. When we worked together on the children’s version of that book, I suggested to Joe that they start a Junior SeaDocs. JuniorSeaDoctors has taken off and really driven home the power of writing these kinds of books. We’ve got a curriculum now, we raised money to get the books for free into all the 5th grades in the Puget Sound area, and now we’re expanding that to the whole state of Washington. In this time of homeschooling and broadening horizons, we’re ready and up and running!

MH: If WHSRN partners are looking for creative natural history education ideas during this time of homeschooling, is that book available beyond Washington State?

ADB: Oh yes, absolutely. Explore the Salish Sea: A Nature Guide for Kids is available, as are all the workshops, curricula, and other resources on the Junior SeaDoctors website.

My next goal with Pacific Flyway is to raise the money to do a Spanish translation. I feel it’s critically important. It dishonors half of the Americas not to do that. I really am excited to turn our attention to that in the next year. It’s just a matter of surviving the COVID-19 era and moving into the next phase.

MH: I know that would be hugely appreciated by many WHSRN site partners. You were able to visit so many WHSRN sites as part of this project. Did you discover any examples of site stewardship, habitat protection, or outreach efforts that you found especially inspiring?

ADB: I think the richest experience I had was meeting with the people on Chiloé who are conducting research and outreach there. That opened up my eyes to the WHSRN’s extraordinary reach. It was so powerful to me because this was my third trip to Chiloé, and there was a decade between my second and my third trips. I witnessed extraordinary degradation of critical wetlands that occurred during that time, and shorebird numbers were down. But in that time, the grassroots organization CECPAN was founded (The Center for the Study and Conservation of Natural Heritage, or Centro de Estudio y Conservación del Patrimonio Natural in Spanish).

I sometimes feel like there’s a divide between scientists and the general public. And in a way it’s a self-imposed division by people who don’t feel they bring enough science background to any discussion, so they sort of step back or they see scientists or researchers in general as just talking to each other. That’s what is not happening on Chiloé, at least not in my experience of being there, with everything we saw. It was amazing to see the work that has been done and some of the most important estuaries being preserved. You see the effect of private philanthropy in combination with conservation organizations like WHSRN – and seeing that is so powerful.

One of the things that was so extraordinary on Chiloé were these murals done by a well-known Chilean muralist of the estuaries and the birds, on the outside walls of schools. And when we walked through the schoolhouse, the hallways were lined with the kids’ artwork, which said “our birds.” The kids refer to their shorebirds, and their estuary. They’re taking ownership. I’d like to see that happen here in the US.

Shorebird Mural in Chiloe. Photo: Audrey Benedict

MH: You’ve said that this book is an urgent call for conservation action. What message would you want to pass on to WHSRN site partners who are working so hard to protect shorebirds across the hemisphere?

ADB: That’s a very good question. I would really like to emphasize mentorship. For your colleagues in the field, I mean mentoring each other as well as taking the opportunity to mentor people in the communities where you’re working in a one-on-one way. It doesn’t cost anything and it’s incredibly powerful. I can’t count the number of mentors I have had in my lifetime, but each one added a facet to what I do now. Keep on mentoring newcomers who come into the research field, students, and the general public in these communities. That’s how we build relationships, and these relationships I believe have to have an emotional connection to work. The kindness that Jim Chu showed me is an example of that. I can’t begin to give anyone suggestions about how to do their work. I’ve never called myself a scientist, I’m a naturalist. But sometimes that’s a good bridge to cross.

Cover Photo: Western Sandpipers roosting. Photo: Florian Schultz.